While some people have nice plans for a getaway, Sarah Baatout is aiming straight for the planet Mars.

The Director of the Radiobiology Unit at SCK CEN (Belgian Nuclear Research Centre) for more than 20 years is committed to deciphering the behaviour of the human body under extreme conditions, which is a prerequisite for long-duration flights in space, and in particular, in dealing with cosmic rays.

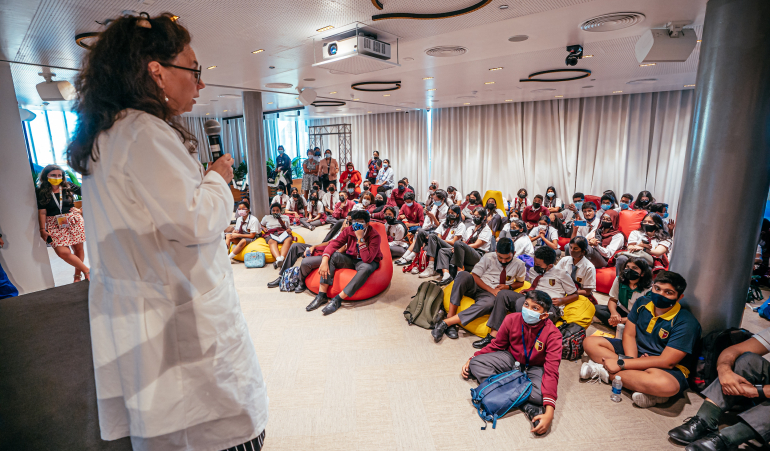

Space revealed a few of its secrets to the lucky people present at the Belgian Pavilion during Wallonia-Brussels Week at the Dubai World Expo, who were able to listen to Sarah Baatout's Masterclass on aerospace in Wallonia and Brussels. They also learned that an expedition to Mars was a long, perilous, and expensive adventure. A space conquest is a miracle; large numbers of researchers are working on as many questions as there are stars in the Milky Way.

The question nagging at Sarah for a long time concerns the physical disturbances that affect our bodies, in particular our immune and cardiovascular systems when they are confronted with extreme confinement conditions: stress, isolation, weightlessness and prolonged exposure to cosmic radiation. These are the conditions that astronauts will encounter on their way to Mars and back. "I have been interested in what goes wrong in the human body for a long time," says Sarah Baatout. "As a child, I was fascinated by the horrible pictures of diseases in the encyclopaedias I used to look through at home. I wanted to find solutions for these diseases. I could have gone into medicine, but I chose research, where science and health come together."

Sarah Baatout turned to biology and then radiobiology and its application in the treatment of cancer, where progress has clearly reduced side effects. "Today, cancer treatments are much more effective and targeted," continues Sarah Baatout, "we are in the process of adapting protocols according to the site of the body and the stage of the disease, but in the future we will be able to adapt them according to each patient and their radioresistance by developing biomarkers, just as we do for an astronaut by studying their ability to resist ionising radiation in space. It is essential to know how many times they will be exposed to radiation and take 'spacewalks on the surface of the Moon', not to mention a trip to Mars where they will be confronted with deep space, a combination of galactic, solar and cosmic radiation that cannot be stopped and that passes through everything. Not only is this radiation dangerous, but space is also a place that amplifies problems," continues Sarah. "We know about accelerated skin ageing and the disrupted circadian rhythm since in orbit the sun appears every 90 minutes, but there are also cardiovascular problems or new allergies due to the increased level of immunoglobulin E. We need to understand all the mechanisms, especially since the immune system is weakened in space, which can quickly create major problems".

Just as the microbiome of our intestines reacts very differently in zero gravity, Sarah Baatout has also studied the stability of the drugs astronauts have taken on space missions and their resistance to radiation.

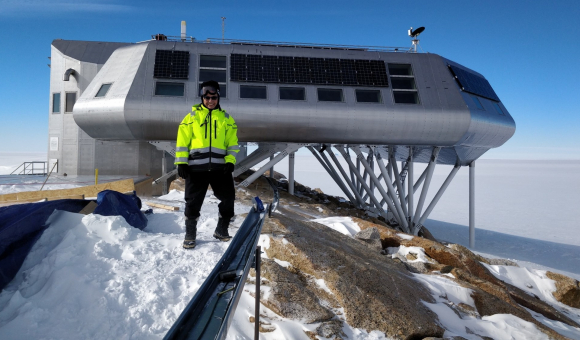

"We conducted several studies during our mission in Antarctica a few years ago, in the heart of the Princess Elisabeth polar research station. Although it is impossible to recreate the space environment, Antarctica is a good test, especially of extreme confinement conditions. We were able to study the properties of spirulina, green algae already used by astronauts as a dietary supplement and which could have a beneficial effect on intestinal flora damaged by stress. Up to 10% of the food for future space missions could be spirulina-based."

One of the most ambitious of the space projects in which SCK CEN is involved is the Melissa consortium, which began in 1989 and will not be completed until 2030 at the earliest. This project aims to make astronauts self-sufficient by making it possible to produce oxygen, water and food in a loop.

The visiting professor at Ghent University and KU Leuven would also like to extend her research into space. Sarah Baatout has therefore applied to be part of the next mission to the moon in 2024 and to Mars in 2035. The sky is the limit. For this enthusiast, it would be more like infinity and beyond.

By Catherine Haxhe

This article is from the W+B Magazine no. 157.