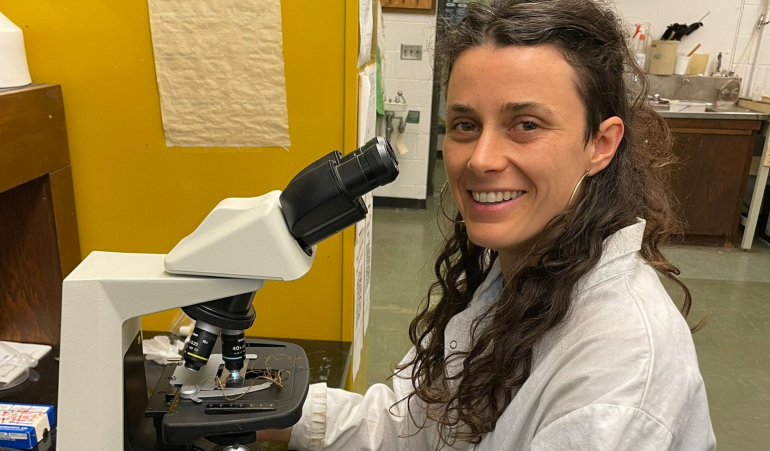

For the past two years, Brussels-based bioengineer Sasha Pollet has been studying the relationship between plants and the characteristics of the soils in which they grow, as part of her PhD in Canada.

"I'm focusing on root systems," she says. "The general idea behind my work is to get a better understanding of how, in relatively nutrient-poor soils, plants manage to grow optimally. A situation which is far from that of our modern agriculture, which is ultimately based on rather... lazy plants."

Fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation: assisted plants

"In modern agriculture, we cultivate plants to which the farmer supplies everything they need to thrive, like fertilizers and pesticides. And even irrigation in some regions. As a result, the plants are happy. They grow well and the yields are excellent. In the end, the soil is only used as a substrate."

"When you analyse this system, you can see straight away that it's neither resilient nor sustainable," says Sasha Pollet, who has been doing her PhD at the University of British Columbia (UBC) for the past two years thanks to a WBI World scholarship

Developing more resilient agriculture

"In a natural forest, on the other hand, as here in Canada, in the rain forest, we can see wonderful biodiversity, grandiose trees and incredible biomass. And all this grows in a soil that's actually quite poor and has not benefited from any external anthropogenic input. This is where the idea of studying these natural systems came from, to learn from them and inspire more resilient agriculture.

In Professor Jean-Thomas Cornélis' soil science laboratory at UBC, the researcher is interested in root activity. Plants growing in slightly limiting conditions develop several natural processes to make the most of their environment. For example, by enhancing their root system to make it more efficient at capturing nutrients from the soil. Sometimes in symbiosis with soil micro-organisms.

Promoting root exudation

This is the overall context of her PhD. If we slightly reduce fertilizer inputs in agriculture, would that not maximise the natural processes within the plant? Leading the plant to search for some of its nutrients itself? "So, I'm studying the effect of different soil types and lower fertilizer inputs on root exudation," explains Sasha Pollet.

While roots capture nutrients from the soil, they also release certain compounds into it. This is called exudate. This is an organic compound that depends not only on the type of plant in question, but also on climate, soil composition and nutrient requirements.

When plants are put under stress, they produce more exudates. "This is what enables the plant to interact with its environment, for example with micro-organisms and soil particles. These exudates can dissolve the soil minerals the plant needs, which it will then capture," explains the bioengineer who originally trained at Gembloux (ULiège).

The white lupin as a study model

"I'm using the white lupin as a study model. Under limiting conditions, it tends to release a lot of exudates – mostly carbon, which is then stored in the soil. This is also something we're interested in as a way of storing atmospheric carbon in the soil, to combat climate change. But now we're getting into other considerations."

During her first years as a doctoral student, Sasha Pollet carried out two experiments with white lupins, in hydroponics and soil cultivation. The aim was to determine to what extent an optimised reduction in external fertilizers (phosphorus in this case) led the plant to develop its root system and increase exudate production, thereby fetching the nutrients naturally present in the soil, all while preserving yields.

Famenne soils are not the same as those of Hesbaye or Condroz

Aiming for a better understanding of how plants interact with the soil. But also, perhaps, to bring about changes in current agricultural practices, by optimising the use of fertilizers and the capacities of the roots themselves.

"To achieve this, we also need to take an integrated look at all the other parameters involved," adds Sasha Pollet. She's thinking about soil formation, soil development, plant development and the plants' impact on the soil, and so on. "We need to develop a more holistic approach, which requires multiple experts," she says.

"Only then will we be able to use the exudate phenomenon to develop more resilient agriculture, one day. This requires a thorough understanding of soil-plant relationships. And every soil environment is different. In Wallonia, for example, exudates will impact the soils in Famenne, Hesbaye and Condroz differently," she concludes.

Source: Article by Christian Du Brulle for Daily Science